“What was their crime?”

Storytelling goes both ways.

“We get to be real with our stuff, too. ”

— One Parish One Prisoner team member

TELLING THE STORY

Part of being incarcerated is having to face your past, your harmful actions. It's less hidden. The charges are public. And if anyone wants to get to know you, while in prison, they generally know you did something, you were charged with a crime of some sort.

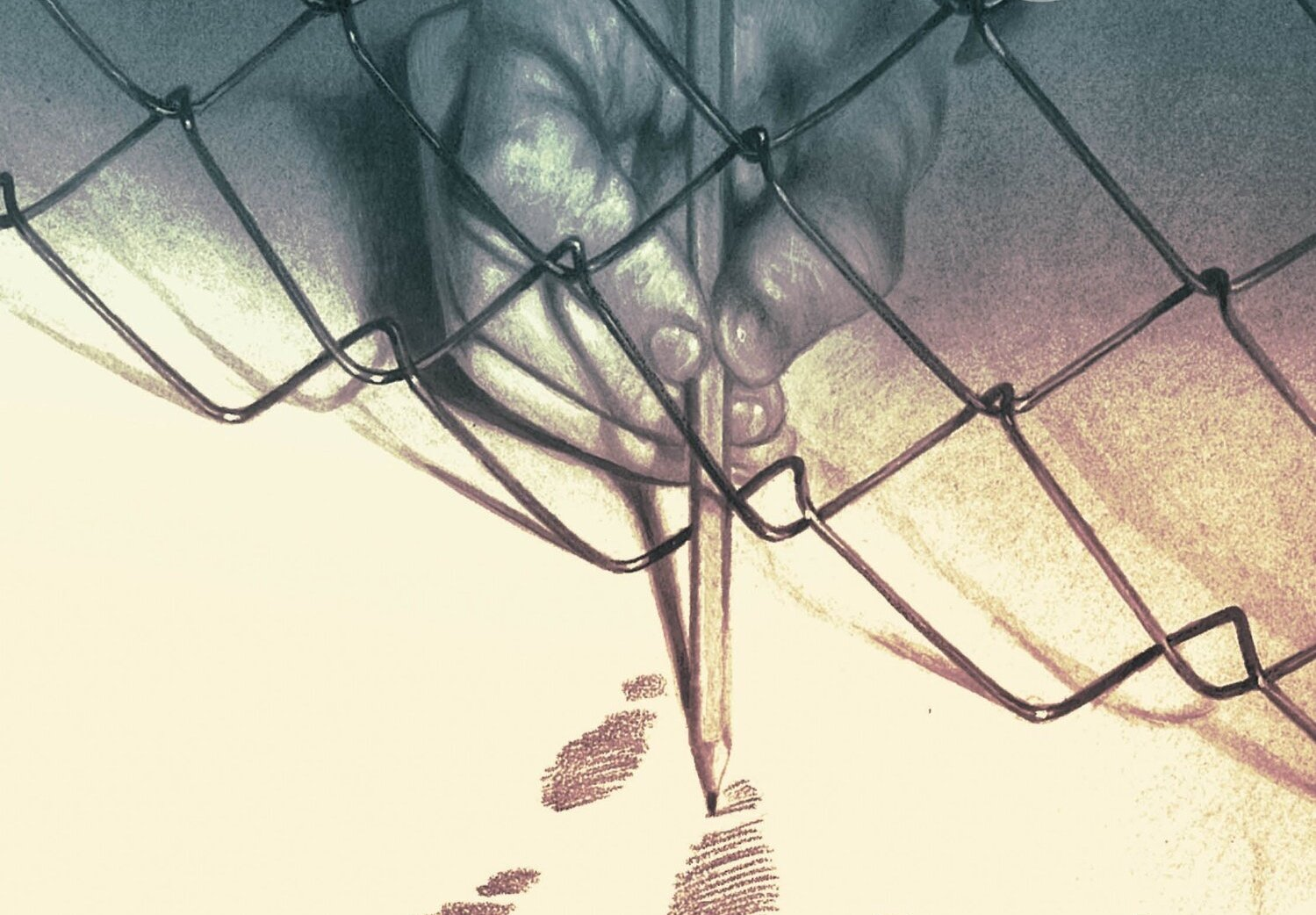

That unspoken awareness of one group being Guilty Of Something (as opposed to the rest of “us”?) is the invisible gulf separating “Us” from “Them.”

It's a question not only lawyers and judges ask before sentencing, but friends, family, employers, and probably you yourself, still have the same question: "What'd you DO?" “What are you in for?”

As a chaplain for many years, I never felt a need to know. I don’t really care.

But as we've worked with more One Parish One Prisoner communities building relationship with someone inside a prison, I've found it's a question that eventually must be confronted. To build trust. That is, trust for one side of the walls.

So we might as well take this as an opportunity to do it well.

To answer that question of the past, the harm done—besides letting people Google public records and old newspapers on their own—requires courageous storytelling.

What was happening in my life that led to this act, or to being in here? And if there's been a change, What was the awakening, the healing, the process? That's the heart of any story: Where the plot turns. Where the character begins to transform.

Better to let our currently incarcerated brother or sister tell their own story in their own words, and break through the dark fog of online mugshots, lists of charges, and our own fears.

Even the men and women I've known who were falsely accused and wrongly incarcerated—their time inside those walls eventually led them to look at themselves in the mirror. They learned to trace the shape of their story, their past. The light and the dark, both.

“It would be good for me, too.”

Here's the thing: most folks out here in the community, and especially those in churches, have never had to tell courageous stories.

Or, we’ve had the opportunity to tell costly stories that risk shame. Where we aren’t the Good Guys.

Confession is a lost practice today.

So if we want to invite our incarcerated brothers and sisters to share their story with us (especially the story of their past, their crime, and what changes have begun in them), why leave it one-sided?

“So basically, our own crimes?

We just didn’t go to prison for it.”— OPOP team member

Many churches have understandably not dared to ask their partner, they tell me. "Because it just wouldn't feel right," they say—to have this person be the only one writing their wrongs.

So let's not make them the only one.

One team, preparing to support their new friend through immigration proceedings, realized when talking to a lawyer that they would need to know Antonio's full story in order to show the courts they aren't naive church folks getting manipulated.

“So that it’s not superficial,” one man summarized. “To show that we really know him.”

“Isn’t that what we all need?” another woman said in the Zoom call meeting. “I mean, we are great at superficial relationships. And we all want to build more meaningful ones, really know each other. Right?”

Bingo.

Or, as Father Greg Boyle says: “Kinship so quickly.”

So as they invited Antonio to tell this story in a letter—the gang years, the night of the robbery, the childhood that led to that, the journey of change he's on now—this beautiful team said they wanted to be together with Antonio in the process. They would write their own short stories of confession and personal healing. To share with Antonio. And with each other, if they want.

Some have already said this was something they've always needed to do. For themselves. And they've never had an opportunity.

Now it's part of what we do.

“I’ve written to A. two, long letters basically ‘writing my wrongs.’ I must say that it was cathartic for me, but also encouraging to A. It definitely levels the ground we both stand on.

And it should come as little surprise from what we know of A, that he has a compassionate, ministering heart and was very encouraging to me. ”— Bill, OPOP team member

READ

This month, read the prologue to Shaka Senghour's raw memoir of redemption, Writing My Wrongs or watch, prayerfully, Shaka’s TedX video above.

WRITE

Then take some time to write a 3-5 page letter responding to one of these prompts:

Shaka begins his larger story at the critical moment when he looked himself in the mirror, in solitary confinement, and knew everything had to change. Was there a moment in your life when you faced something in yourself that was painful to see—and knew things had to change? Describe that moment in your life. What was happening? What had to change? What did you do?

Have you ever hurt someone deeply? A friend, family member, child, stranger? What happened? Did you not see the harm until way later? Did you carry the guilt and shame privately? Is it something you still carry, and haven't known what to do about it?

Is there something you have never opened up to talk about, but you still carry? Maybe it’s not something you did, but was done to you. If you need to start there, start there. Something that carries deep shame? Have you kept it to yourself for fear of being judged? Or you've never had someone who cares to hear your dark secret? This may be your chance.

Some of my friends and even family members have shared heavy stuff with my friends in prison, in their letters. Things they've never told me! Your person in prison might be the safest person you could ever open up to. He or she might be your greatest confessor. They're probably a lot less likely to judge you.

BECOMING SAFE

As we said in the Art of Building Trust module, churches sadly don’t always have a reputation for being safe places. Too much hiding, too much pretending. Too much fear of judgment. Even if there’s no outward culture of condemnation, churches can reward mask-wearing. It’s not a place where outsiders nor insiders feel they could bring their full self, mess and all.

But this letter you and your team are each writing—it’s not just solidarity with your incarcerated friend, not just healing for you. This is a practice in welcoming more reality, listening to each other.

This is an exercise in disarming ourselves of judgment. And risking being received.

Also, it’s a practice in transparency. Another reason churches aren’t safe is that we are so good at hiding and keep up appearances. Sunday school teachers and pastors and parishioners can commit all kinds of abuse. It festers until it eventually blows up. What if we had better practices in safely telling and hearing each other’s wrongs?

We might become places of healing rather than hiding.

ACKNOWLEDGE. APOLOGIZE. ATONE.

Those were the three steps Shaka Senghor prescribed in the video. He’s not even a Christian. But we get so numb to words like “atonement” in sermons that we sadly haven’t become great at practicing atonement in our world. Nor confession and forgiveness. Before we can get there, let’s start with the first part: acknowledging. How we’ve been hurt. And/or how we’ve hurt others.

What better trainer could God give you than your incarcerated friend already doing just that with you?

FOR TEAM DISCUSSION

Talk together about what you think of this proposal. Does it excite you? Bother you?

What would help you each move forward and take a step—write something—that challenges you deeper into opening and unburdening with your underground friend?

Anyone want to share what’s already coming up? This can give others courage. And ideas.

Do you think Christians have enough opportunities to practice courageous storytelling, confession, and atonement? If not, why not?

Do you as a team want to share what you write with each other? Or just confide with your incarcerated partner?